INTRODUCTION

This story didn’t start with Apple Silicon.

It started in the 1990s, when Apple already tried to take on Intel once. And back then, Apple lost.

That part matters. Because what’s happening now feels familiar, but the outcome might not be the same.

.Apple Mac G3.

Apple’s First RISC Gamble (1990s)

In the 1990s, Apple bet big on RISC architecture to take on Intel’s x86 chips. Apple partnered with IBM and Motorola in the AIM alliance to create PowerPC processors for Macs. Back then, RISC chips like PowerPC promised simpler designs and higher efficiency, while Intel’s x86 was seen as complex (CISC) but entrenched. Apple even ran cheeky ads like the one with a snail carrying an Intel chip claiming its PowerPC Macs could outrun Intel PCs[2]. And for a while, PowerPC Macs were competitive. Early Power Mac models with PowerPC CPUs delivered strong performance, giving Apple enough confidence to poke fun at Intel.

So what went wrong? Simply put, Intel kept improving at a relentless pace. Former Apple CEO John Sculley later admitted that not going with Intel earlier was a mistake, because Apple “did not foresee Intel’s ability to improve x86’s CISC architecture to match RISC”[3]. In other words, Intel figured out how to make its chips much faster and more efficient, erasing many of RISC’s theoretical advantages. By the early 2000s, Intel’s Pentium and Core series chips were leaving PowerPC in the dust, especially in laptops where Intel’s focus on power efficiency paid off. Apple found itself stuck with PowerPC G4/G5 CPUs that ran hot and weren’t keeping up in performance-per-watt. Apple couldn’t get a PowerPC chip to work in a lightweight Mac laptop the way it wanted.

In 2005, Steve Jobs finally made the tough call: Apple would switch from PowerPC to Intel processors for the Mac. Jobs explained that Intel’s roadmap looked far better and that Apple simply couldn’t build the products it envisioned on the PowerPC roadmap[4]. (Translation: IBM/Motorola couldn’t deliver a cool, fast G5 for Apple’s notebooks, among other issues.) Going Intel also meant Macs could natively run Windows a nice selling point at the time[5]. This move ended Apple’s first RISC vs x86 battle. Intel had won that round, and from 2006 onward, Macs ran on the same brains as Windows PCs.

.Intel Pentium II.

The Intel Era and AMD’s Rise

Once Apple joined the Intel camp, the computer world settled into an x86 duopoly: Intel and AMD. Intel dominated the market for years, but AMD kept pushing as the scrappy rival. In the mid-2010s, Intel hit some stumbling blocks (like delayed chip advances), and AMD seized the moment with its Ryzen and Epyc processors.

.First Macbook using Core 2 Duo in 2006.

By completely redesigning its CPU architecture (the “Zen” core), AMD achieved big jumps in performance and efficiency. Suddenly, AMD’s chips were often as fast or faster than Intel’s, and offered more cores for the money. This wasn’t the 2000s era of AMD being just the budget option, AMD became the performance leader in many cases.

The numbers tell the story. As of 2025, AMD has captured over 25% of all x86 processor shipments, an all-time high for the company, while Intel holds around 74%[6]. In the lucrative desktop PC segment, AMD’s share recently hit 33.6%, roughly one-third of the market[7]. And in servers, AMD Epyc chips have made serious dents in Intel’s dominance, thanks to strong performance and core counts. In short, x86 isn’t a one-company show anymore AMD reinvigorated the x86 platform just when Intel was losing steam. This competitive fire has forced Intel to innovate more (with moves like hybrid “big.little” core designs in 12th-gen Core chips and accelerating its roadmap). For PC buyers, the result is that x86 CPUs today are faster and more efficient than ever, whether you go with Intel or AMD. The x86 camp has proven it can evolve; it’s not standing still.

An AMD Ryzen CPU. AMD’s Zen-based processors have challenged Intel and grabbed significant market share in the x86 world[7].

It’s worth noting that back in 2005 when Apple switched to Intel, some wondered “why not AMD?”. Apple reportedly talked to AMD but AMD didn’t have a low-power chip suitable for MacBooks at the time[8]. Intel simply had the better mobile CPUs then. Ironically, today AMD is very focused on efficiency (see its laptop Ryzen chips or the 64-core Epyc server CPUs), and has even developed special 128-core server chips (codenamed Bergamo) aimed at cloud efficiency. AMD’s CTO Mark Papermaster has argued that Arm (the RISC architecture behind Apple’s chips) isn’t inherently magic, it’s about design trade-offs. If you tried to give an Arm chip all the high-performance features of an x86 chip (like super-wide vectors, out of order heft, and multi-threading), the Arm chip would “grow significantly” in size and power use[9]. In other words, x86 chips can be made more efficient for specific uses, and Arm chips can be made bigger and more powerful both approach each other given enough engineering. AMD proved this by creating a more efficient Zen 4c core for cloud CPUs, essentially trimming some performance to double the core count. The takeaway: x86 is adapting to fight back on efficiency, while Arm is scaling up in performance.

.AMD Ryzen 2017 - Today.

Apple’s Second Try: Apple Silicon (M1 and beyond)

Apple didn’t forget the lessons of the 90s, it just waited for the right moment to try again. That moment came in 2020 with the launch of Apple Silicon M1. This time, Apple’s bet was on the Arm architecture (the same RISC lineage as many mobile chips). But unlike the PowerPC days, Apple now designs its own Arm-based chips in-house, giving it total control. And here’s the thing: the M1 chip shocked everyone. It was really, really good. Apple’s first generation of M-series chips (M1, followed by M2, M3, etc.) delivered high performance while sipping power, thanks to Apple’s expertise from years of iPhone chip development. Suddenly, a MacBook Air with an M1 could outrun older Intel Core i9 MacBook Pros in many tasks, while staying cool and silent. Even the earliest M1 Macs in 2020 were beating the fastest Intel laptop chips Apple had used and those M1 machines weren’t even the “Pro” models[10]. The higher-end M1 Pro/Max/Ultra and later M2/M3 generations only widened the gap.

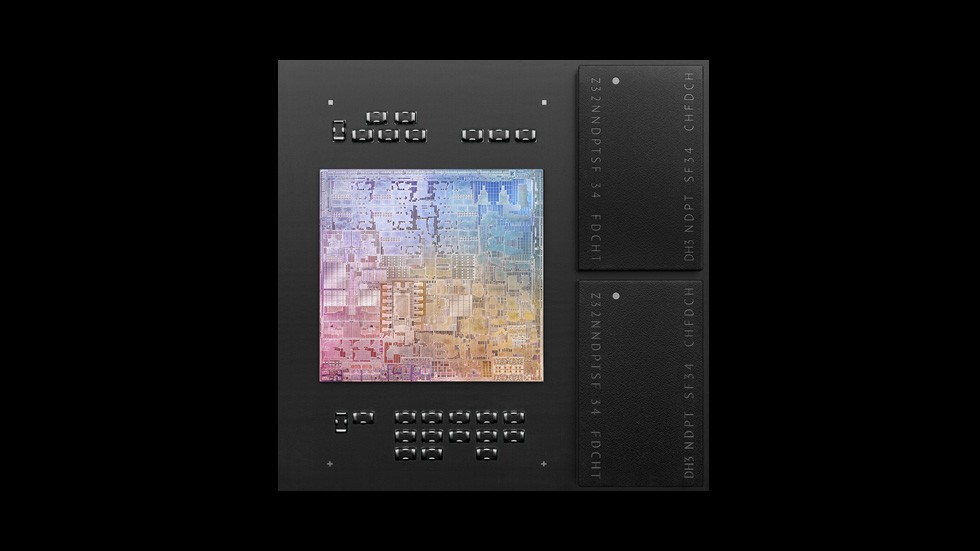

Apple’s M1 system-on-chip (center) on a Mac logic board, with two black unified memory modules adjacent. Apple’s tight integration of CPU, GPU, and memory allows huge performance per watt gains[10].

This wasn’t a fluke or marketing spin; independent benchmarks confirmed it. By 2025, Apple’s M-series chips in Macs have proven themselves. For example, the M3 and M4 chips (Apple’s 3rd- and 4th-gen silicon) in iMacs and MacBook Pros are outpacing equivalent Intel-based models from just a couple years prior. In fact, a mid-range iMac with an M3 can beat a high-end iMac Pro that used a powerful Intel Xeon chip[11]. Apple achieved this by designing chips with a balanced approach, lots of fast CPU cores, strong integrated graphics, and specialized neural engine accelerators, all tied together with unified high-speed memory. And because Apple controls the software (macOS) too, it optimized everything to take full advantage of the hardware. It’s the kind of vertical integration that PC makers (relying on off-the-shelf Intel/AMD chips) can’t easily match. Apple basically brought the efficiency of iPhone chips to the PC world, and it was a wake-up call for the x86 side.

So now we’re in a situation that feels oddly familiar: Apple has a RISC-based chip that’s threatening the x86 incumbents. Only this time, Apple isn’t trying to sell chips to other computer makers or convert the whole industry, it’s simply using its chips in its own popular products. That alone is enough to sting Intel, since every Mac sale is one less Intel CPU sold. And it’s not just Apple: Arm-based chips are popping up elsewhere, like in servers (Amazon’s AWS Graviton and Ampere Altra CPUs are Arm-based and boast great per-dollar performance in the cloud). The momentum behind Arm is real now in a way it wasn’t in the 90s. Back then, RISC chips were niche outside of Apple and some workstations.

Today, Arm chips power essentially all smartphones and tablets, and are pushing into laptops and servers. That gives Arm a massive ecosystem and economy of scale. Microsoft has even been working on Windows for Arm, preparing for a future where PCs might not all be x86. In short, x86 now faces a broader RISC offensive, not just from Apple but from the whole mobile-driven world of chip design.

.Apple M1 Chip.

x86 vs. Apple (ARM) – Who Wins This Time?

And here we are: Apple’s M-series vs Intel/AMD’s x86 chips, round two. Will x86 “come out on top” again as it did in the 90s/2000s? Or is this the start of Arm (and RISC) taking a lasting lead? The realistic answer is a bit of both. x86 isn’t going away quietly. Intel and AMD have huge resources and decades of software compatibility in their favor.

Most Windows applications and games are still optimized for x86, most data centers run x86 code, and that legacy advantage won’t disappear overnight[12].

In scenarios where pure single-threaded speed matters (like high-end gaming or certain engineering software), the fastest x86 chips still shine, modern Intel and AMD CPUs can boost to 5.5-6 GHz, whereas current Arm-based designs (including Apple’s) top out at lower clock speeds[13]. x86 chips also support features like AVX512 and other heavy-duty instruction sets that some pro software relies on[14].

These are areas where x86’s long history provides an edge in peak performance and specialized capabilities.

On the other hand, Arm’s strengths play to modern needs. The efficiency of Arm architecture (and the willingness to use lots of smaller cores) means chips like Apple’s M2/M3 or server CPUs like Ampere can do more work per watt of energy. In large data centers, an Arm server CPU might use 20-40% less power than a comparable x86 chip for the same work[15], a huge factor for cloud providers watching electric bills. And in laptops, Apple has shown that you can have both high performance and all-day battery life using Arm-based silicon, which flipped the old script that “PCs need fans and lots of heat”. Plus, designing chips in-house lets Apple tailor its CPUs to what its software needs most, something off-the-shelf x86 chips can’t do as specifically.

It’s also important to note that AMD and Intel are adapting. Intel, for example, is borrowing a page from Arm’s book by adopting hybrid architectures mixing efficient cores and performance cores (similar to Arm’s big.LITTLE approach) to improve power efficiency in 12th-gen and newer Core processors. And AMD, as mentioned, has introduced chips with tons of smaller cores for cloud workloads. In other words, x86 is becoming more Arm-like in some ways (efficiency), while Arm designs are becoming more x86-like in others (higher performance). The line between what is strictly a “mobile chip” and a “PC chip” is blurring.

So, will Intel x86 bounce back and “win” again? It’s not 1995 or 2005 anymore and the landscape is different. Apple doesn’t need to convert the whole industry to Arm; it just needs to keep making excellent chips for its own growing base of Mac users. And it’s doing that the latest Mac sales have been strong, and Apple now has around ~10% of the PC market, with especially high share in premium laptops. Intel and AMD, meanwhile, will continue powering the other ~90% of PCs and all the custom-built gaming rigs and enterprise servers out there. They’re not standing still, and we’re already seeing x86 chips improving in response to competition. In fact, competition from both Apple and AMD has lit a fire under Intel in recent years. Intel has been investing heavily in new chip designs and even exploring using external fabs (like TSMC) to regain a manufacturing edge. By 2025, Intel’s latest roadmap shows it aiming for aggressive leaps in performance and efficiency to catch up.

Here’s the thing: We might not see a total victory by one side; instead, expect coexistence and specialization. Apple’s ARM-based Macs will keep carving a nice chunk of the market, especially among users who value battery life and tight integration (and who are in Apple’s ecosystem to begin with). x86 PCs will continue to dominate areas where compatibility and raw throughput matter, high-end gaming, many professional applications, and servers although ARM will nibble into some of those via specialized chips. We could even imagine a future where both architectures thrive: x86 for its strengths, Arm for its strengths, possibly even in the same environments for different tasks. (And who knows, by the time this plays out, a wildcard like RISC-V might emerge to shake things up further – an open-source RISC architecture gaining momentum, but that’s a story for another day.)

In the 90s, Intel decisively won against the RISC challengers. In the 2020s, the competition is much tougher. Apple has already proven it can beat Intel in its corner of the ring. The question now is how Intel and AMD respond over the coming years. The good news for consumers is that this fight is driving faster innovation. We’ve gone from worrying about slowing CPU progress to seeing a flurry of amazing chips from all sides. Will x86 come out on top again? It might hold its top spot in market share for a long time, thanks to legacy and momentum, but in terms of technology, it’s clear x86 has a real fight on its hands this time. Apple’s M-series isn’t a one-off experiment; it’s a roadmap Apple is fiercely executing.

That said, I wouldn’t count Intel/AMD out. They’ve faced scares before (remember Itanium? Or the first wave of mobile computing?) and adapted to survive. We could very well see x86 chips that surprise us with new designs or even some hybrid x86/ARM approaches. And AMD’s recent success shows x86 can reinvent itself, it went from underdog to top dog in performance in a few short years by rethinking design. As Papermaster suggested, there’s nothing stopping x86 from being efficient, given the right design goals[9]. In the end, there may not be a single “winner”. Instead, we’ll have a competitive landscape where Apple’s ARM-based Macs push the envelope on efficiency and integration, while Intel and AMD push the envelope on compatibility and raw horsepower and each learns from the other.

And that’s why it matters: this renewed rivalry means better computers for all of us. Apple vs Intel round two is driving everyone to do their best. In a way, x86 winning in the 2000s made Intel a bit complacent now with Apple (and AMD) nipping at its heels, x86 might come back stronger, or at least keep us techies well entertained. One thing’s for sure: it’s an exciting time to be a CPU nerd, because the chip war is on again only this time, the old champion x86 is facing a challenger that already tasted victory on your desk[10]. Game on, silicon warriors!